It’s a process we all go through in one form or another; these stories of recovery will sweep you away.

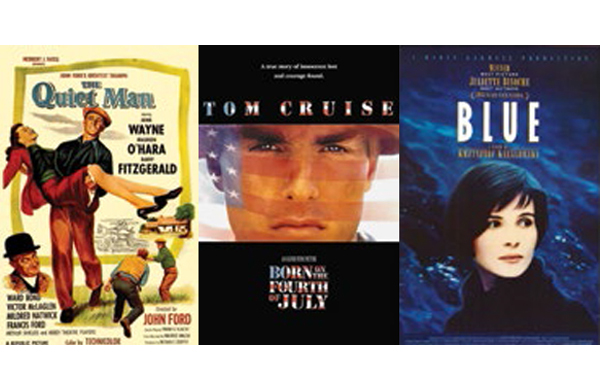

The Quiet Man (1952)

After a professional tragedy ends his boxing career, American prizefighter Sean Thornton returns to his childhood homeland in search of healing. The place is called Innisfree (any associations with Yeats are entirely intentional), and the greener-than-green backdrop could only be the Ireland of director John Ford’s imagination. John Wayne is in gentle-tough form here as Thornton, who seeks to reclaim a bit of ancestral land and becomes bewitched by feisty local colleen Mary Kate Danagher (Maureen O’Hara). The 1952 film’s action is writ large, and there’s no question the Irish folk are vivid stereotypes — but this is a fantasy, a comedy of behavior filtered through Ford’s unfailingly poetic gaze. In Ford’s eye, the soul is in land and community, two things his hero badly needs. Bonus: Barry Fitzgerald executing one of the all-time great reaction shots as he looks upon a happily broken marital bed.

Born on the Fourth of July (1989)

The real-life memoir of Ron Kovic is a harrowing one, and Oliver Stone’s 1989 film adaptation is suitably unflinching. Having gone to Vietnam as a gung-ho youth, Kovic (played by a completely committed Tom Cruise) is paralyzed in battle and haunted by guilt over his own actions; he returns to the States looking for purpose. A role in the anti-war movement awaits, but not before experiencing hellishness that seems to go beyond even the nightmare of combat. Stone’s touch is not subtle, but as a Vietnam vet himself his fury is certainly earned. As we watch Kovic’s difficult passage, we might glimpse the metaphor for any journey back from serious damage and disillusionment. The life story is specific to a time and place, but the resonance is universal.

Blue (1993)

A woman loses her family in a car accident; her recovery goes not at all according to plan. She tries to shed the associations of her former existence by moving to a new neighborhood in Paris and starting over — but she can’t truly get away from her life. Her late husband’s unfinished business (he was a composer) is still hanging over her, and his other baggage returns in all-too physical form. Much of this character’s struggle to find herself plays out across the calm, meditative face of Juliette Binoche, who has perhaps never been better. This is a film of silence and reflection, and director Krzysztof Kieslowski is not interested in spelling out every single meaning here (this 1993 film is part of the filmmaker’s slightly-connected trilogy called Three Colors; the other segments are Red and White). As somber as the film is, Roger Ebert might have been onto something in calling Blue an “anti-tragedy.” We look into Binoche’s contemplative face and are free to project our own feelings and thoughts there: sorrow, hope, disillusionment, renewal. That’s a bold place for a movie to go, but it makes us into active, not passive, viewers — and perhaps it’s an honest suggestion that recovery is never really achieved but an ongoing human process.