Many years back at a book sale in a pretty town in Austria, I bought a stack of Baedeker’s red guidebooks. I paid for four of these fragile, red, cloth-bound little volumes and a Flaxman’s Hand-Book of English and German Conversation. The Flaxman’s is from 1907; the Baedeker’s are also from the early 1900s. I think they all belonged to the same person, a Doktor Ernst Fusching of Scharding am Inn, a town near the current border between Austria and Germany. Herr Doktor’s name is rubber stamped in slightly smeared ink inside the cover of each book, save the phrase book — that appears to have spent a bit of time at an antique book store in Vienna, Franz Malota on the Wiednerhaupstrasse in the fourth district. A blue stamp on the fly leaf tells me so.

Speak to Me of Days Past

When I got the books home, I spent much too long annoying my German-speaking husband by butchering translations of such awkward phrases as, “I hope she will find relief from the change of weather,” and “These beavers are light and yet so strong that they will last a long time,” and “Light a fire in my room and tell the chambermaid I should like to have my bed warmed.” The book is divided into sections that provide some context — discussing health, buying a hat, dealing with the hotel staff — but the oddity of these weird little sentences delivered out of context sent me into fits of hysteria.

When in my travels will I ever need to say, “When my servant comes to pay you, he will bring you this old hat to be dressed”

I remember paging through my brother’s Chinese language texts and having the same reaction over the example, “The Loess plateau is very windy at this time of year.” My brother insisted that yes, it did get very windy out there, but I still couldn’t get my head around a scenario in which this particular phrase would prove to be necessary. When in my travels will I ever need to say, “When my servant comes to pay you, he will bring you this old hat to be dressed” auf Deutsch? I still get great pleasure out of flipping through this battered little book to find exactly the right words for expressing my enthusiasm for the White Cliffs of Dover when arriving by steamer or for describing the horse I have in my stables back home.

A Century-Old Must-See List

The guidebooks are a bit more familiar, packed with tiny text that lists the cafes and restaurants, population numbers, major historical turning points, hours and fares for the sailings of steamboats and railways; the usual array of facts, facts and more facts. The pages are interspersed with beautifully engraved maps on yellowed paper; the parks are patterned differently than the mountains, which are patterned differently than the rivers; the buildings and streets are marked in a fading brick orange. Now and then there is a floor plan for a monumental museum or church so you do not miss that critical painting by a Middle Ages master in salon three on the second floor. The occasional fold-out has the waterways printed in the palest blue. The pages are soft and smell just like old books do, of dust and time.

They are like hotel room bibles in their economy of space and use of paper.

The guide to Switzerland has several large panoramic fold-outs — I suppose you were to have stood at the correct view point, book in your gloved hand, calling each of the peaks by name, perhaps holding up your eyeglasses so you could read the tiny, meticulous script squeezed in over each sharp point. They are so pretty, these pages, and thin as cigarette paper, and I am a little nervous every time I unfold them, but they continue to hold up and not crinkle like dried leaves. Here is the Mont Blanc range seen from Flegere, the panorama from the Faulhorn, from Langard, from places I have never been, where the glaciers have receded but maybe the guest house still stands, where maybe I can still ride an updated tram to see an unobstructed view of the lake and buy a cup of tea, though certainly prices have gone up since 1905.

These little books are packed with minutia, such as how many minutes the aforementioned mountain climbing tram takes, whether or not the bakery has coffee, and how many taps are at the spring in the tiny pilgrimage church. They are like hotel room bibles in their economy of space and use of paper. They are so fragile, and each page is so packed with six- and eight-point type that they are nearly unreadable. But they were used, all four of them; the maps repaired with browning cellophane. Inside the Riviera guide, there are a few receipts and stamped tickets. Doktor Ernst Fusching, and perhaps his bride, ate a meal at the Hotel Guillaume Boissett, an inn that specializes in seafood and offers hot and cold-running water. I know this because the receipt from their stay tells me so. The Fuschings visited the Roman ruins in Orange, the Palais des Papes in Avignon, the museum at Arles, and maybe St. Maximin Cathedral — the name of which is underlined in ink. Sometime in the early 1900s, Doktor and Frau Fusching visited the French Riviera, and I have their guidebook.

Can I Go Back Again?

I wondered, after I acquired these books, if I should travel to Scharding am Inn to see if I might find any references to Doktor Fusching, to see if he had living relatives, aging Austrians who would remember Herr Doktor Grandfather as a man who loved to travel, who spoke excellent French and liked to drink beer in Riviera hotels, but what would I do then?

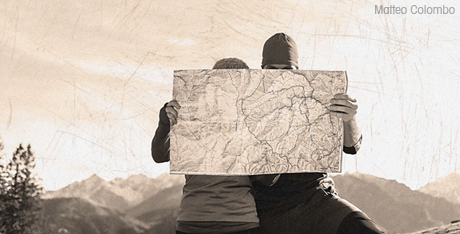

I decided I would rather imagine this turn-of-the-(last)-century man and his imaginary turn-of-the-century wife, the two of them fit and optimistic. I picture them smartly and practically dressed, standing close together at the viewpoint in the slanting late afternoon light. “Look, schatzi, there is Mont Joli in the distance, do you see?” They each hold an edge of the map, delicately unfolded, blocking the wind with their bodies. She looks at it, and then up at the peaks and back to the map and back to the peaks. “Yes, there it is!” she says, and she names all the mountains, pointing across the valley at the granite and ice while time collapses into a rummage sale in a village in Austria and is folded into a guidebook that sits on a shelf in my living room, more than 100 years from “their” now, half a planet away.